Future Development Trends of Aircraft Flight Simulators

Aircraft flight simulators, as the core tool for aviation training and technological research and development, have continuously evolved since their inception in the mid-20th century, driven by advancements in aviation technology, computer science, and human-computer interaction. From early mechanical linkage-based basic training devices to today’s immersive systems integrating virtual reality (VR), artificial intelligence (AI), and high-precision physics engines, the role of simulators has progressively shifted from “auxiliary training tools” to “digital flight capability reconstruction platforms.” Looking ahead, with the explosive growth in the aviation industry’s demand for safety, efficiency, and intelligence, flight simulators are advancing towards more extreme realism, deeper intelligence, and broader application scenarios. Their development trends are not only related to the transformation of pilot training models but are also becoming key infrastructure driving overall progress in aviation technology.

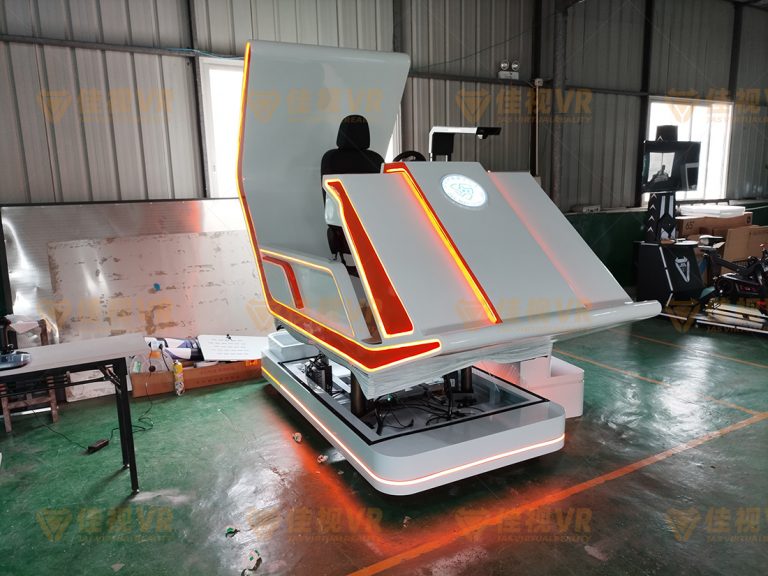

I. Technology-Driven Upgrade: From “Approaching Reality” to “Transcending Reality” in Immersive Experience

The core challenge of traditional flight simulators lies in “replicating reality”—using six-degree-of-freedom motion platforms, high-resolution visual systems, and multi-channel sensory feedback to reproduce force feedback, visual scenes, and acoustic environments during flight as closely as possible. Future simulators will break through the limitations of “approximation,” aiming to “transcend reality” by building a “digital twin flight environment” through multi-technology integration, enabling pilots to receive training experiences in the virtual world that are even superior to real flight.

- The Ultimate Evolution of Visual Systems: From “High Definition” to “Holographic Perception”

Current mainstream simulator visual systems can achieve 4K/8K resolution, wide-angle (over 200°), or even spherical projection. However, limited by optical display technology and real-time rendering computing power, the detailed reproduction of complex weather conditions (such as low-visibility fog, night-time low-light) or extreme scenarios (such as bird strikes, engine fires) still has shortcomings. In the future, visual systems based on light field display technology and Neural Radiance Fields (NeRF) modeling will become mainstream: the former, by recording and reproducing the direction and intensity information of light, allows pilots to “see the terrain behind clouds” or “perceive visual illusions caused by light refraction”; the latter uses AI algorithms to quickly generate physically realistic 3D dynamic scenes from 2D images or sparse point cloud data of real airports and terrain, even simulating “the changing light and shadow effects at the same airport at different times of day” (such as the gradual change in runway reflection at sunrise). More revolutionary breakthroughs will come from the integration of Mixed Reality (MR) and holographic projection. For example, pilots could use lightweight AR glasses to overlay virtual instrument information onto a real cockpit environment (retaining the tactile feel of physical controls), or interact with holographic control panels via gestures in a fully virtual cockpit—this “virtual-real overlay” model can both reduce hardware costs (eliminating the need for expensive 1:1 replica cockpits) and strengthen specific training modules (such as rapid identification of hidden backup instruments during emergencies) by dynamically adjusting the transparency and interaction logic of virtual elements. - “Biologically-Level Precision” in Motion and Force Feedback

Existing six-degree-of-freedom motion platforms can simulate basic attitudes like pitch and roll, but lack precision in reproducing “micro-vibrations” (such as turbine blade resonance) and “non-linear force feedback” (such as differences in impact force distribution at the moment of landing gear touchdown). In the future, new actuators based on piezoelectric ceramics and shape memory alloys will significantly increase response speeds (from the current millisecond level to microsecond level). Coupled with biomechanical sensors that monitor the pilot’s muscle tension and eye movement in real-time, motion commands can be dynamically adjusted—for instance, when simulating “stall buffet,” not only transmitting periodic vibrations to the seat but also simulating “airflow disturbances perceived by the skin” through micro-current stimulation, or even delivering customized balance signals to the inner ear vestibular system via head-mounted devices, achieving “multi-sensory协同 deception” that tricks the brain into believing it is in a real flight stress environment. - “Quantum-Level Accuracy” in Physics Engines

The core of flight simulation is the accuracy of physical models, including aerodynamics (such as the stall characteristics of different airfoils at high angles of attack), engine performance (such as the thrust decay curve of a turbofan engine in high-altitude, oxygen-deficient environments), and system interaction logic (such as backup control paths for flight surfaces during hydraulic failure). In the future, with the integration of quantum computing and high-fidelity CFD (Computational Fluid Dynamics) models, simulators will be able to calculate in real-time phenomena like “local airflow separation when a specific aircraft model passes through mountain turbulence at a specific speed under given meteorological conditions,” and generate personalized control feedback accordingly—this means that differences in flight characteristics of the same aircraft type at different airports, in different seasons, or even with different pilot operating habits can be accurately mapped into the virtual environment, completely moving beyond “generalized simplified models.”

II. Intelligent Leap: The AI-Empowered “Adaptive Training Partner”

If technological upgrades solve the problem of “environmental realism,” then the deep integration of artificial intelligence shifts the simulator from “passively recreating scenes” to “actively guiding learning,” becoming a “digital instructor” and “risk rehearsal expert” for the pilot.

- “Intelligent Generation” of Personalized Training Programs

Traditional training relies on fixed schedules (such as basic takeoff-cruise-landing procedures), making it difficult to precisely reinforce individual weaknesses (such as spatial disorientation, delayed emergency procedure response). Future simulators will be equipped with cognitive state monitoring AI, using eye tracking (analyzing areas of focused attention), EEG sensors (detecting stress levels), and operational data (such as frequency of hesitation in control inputs, amplitude of corrective actions) to assess the pilot’s skill profile in real-time. For example, if the system detects that a pilot frequently exhibits altitude deviations during night instrument approaches, the AI will automatically retrieve the pilot’s historical training data, combine it with common deficiencies among similar trainees, and generate customized training scenarios including “specific visibility conditions + complex terrain airports + sudden equipment failure,” providing immediate guidance during the process through voice prompts (e.g., “Watch bank angle limit exceeded”) or haptic feedback (e.g., right seat vibration alerting for yaw deviation). - “Dynamic Evolution” and “Limit Testing” of Complex Scenarios

Current simulators can preset single failures like “engine failure” or “hydraulic system leak,” but struggle to simulate extreme situations involving “concurrent multiple failures + environmental突变” (such as encountering left engine failure, autopilot disconnection, and communication failure simultaneously in a thunderstorm area). Future AI will possess complex system reasoning capabilities, enabling it to automatically generate dynamic scenarios that are “unpredictable yet conform to physical laws” based on training objectives: for instance, during a transoceanic flight training session, the AI might suddenly trigger a chain reaction: “jet stream in the stratosphere causes sudden airspeed increase → autopilot overload protection disconnects → co-pilot误操作 increases throttle → fuel imbalance warning triggers,” forcing the pilot to make full-process decisions under high pressure involving “priority judgment (control attitude vs. adjust fuel) → multi-system coordinated operation (trim, navigation, communication restoration).” More crucially, AI can gradually increase scenario difficulty through “stress gradient adjustment” (from single to triple failures, from mild weather to supercell thunderstorms), helping pilots break through their psychological and technical comfort zones. - “Emotional Interaction” of the Virtual Instructor

Beyond technical guidance, future simulators will also feature virtual instructors with affective computing capabilities—analyzing the pilot’s speech tone (e.g., increased speech rate when anxious), facial expressions (e.g., frequency of frowning), and body movements (e.g., changes in grip strength on the control stick) to assess their psychological state and adjust communication strategies. For example, if a trainee shows frustration due to consecutive failures, the virtual instructor might use an encouraging tone to break down the causes of errors; if the trainee displays overconfidence (e.g., ignoring warning prompts), it might emphasize risk consequences in a serious tone. This “humanized interaction” not only enhances training effectiveness but also helps pilots adapt in advance to collaboration scenarios in real flight, such as ambiguous instructions from ATC or disagreements among crew members, simulated via multi-role AIs.

III. Application Scenario Expansion: From “Training Tool” to “Core Node of the Aviation Ecosystem”

The value of future simulators will extend far beyond traditional training, becoming full-chain aviation infrastructure covering R&D, operations, safety, and public outreach.

- “Virtual Wind Tunnel” for Aircraft Development

During the design phase of new aircraft (such as eVTOLs, supersonic airliners), simulators can use digital twin technology to rapidly verify aerodynamic layout, control logic, and system redundancy schemes—engineers can simulate “the impact of different battery pack layouts on center of gravity stability,” “lift distribution during failure of a single distributed electric propulsion unit,” or even test “structural response under extreme conditions (e.g., bird strike, lightning strike)” in the virtual environment without building physical prototypes. This “software-first” R&D model can shorten the flight test cycle for new models by over 30%, while significantly reducing the cost and risk of physical testing. - “Rehearsal Laboratory” for Airline Operations

Airlines can use simulators to pre-rehearse “weather adaptability of new routes,” “approach and departure procedures after airport expansion,” or “emergency response to special events (e.g., volcanic ash cloud dispersion, terrorist threats).” For example, before planning a high-altitude route crossing the Himalayas, the simulator can generate “wind shear patterns in different seasons” based on real-time meteorological data, helping crews familiarize themselves with key operations like “engine power decay in low-temperature environments” and “rapid activation of oxygen systems.” During public health events, simulators can also train pilots to execute special procedures like “contactless refueling” and “isolation cabin passenger transfer.” - “Immersive Window” for Public Education and Career Inspiration

With the development of the low-altitude economy (e.g., drone logistics, Urban Air Mobility), simulators will become an important medium for普及航空知识 to the public—using simplified cockpits and gamified interactive designs (e.g., “Simulate a Day in the Life of an Airline Pilot”) to allow ordinary people to experience the rigor of flight control. For youth groups, projects like “Young Flight Engineer” combining VR and programming education can further stimulate interest in aviation technology, reserving future talent for the industry.

IV. Challenges and Outlook

Despite the promising prospects, the development of future simulators still faces multiple challenges: Firstly, the demand for computing power from high-precision physical models and real-time rendering is growing exponentially, requiring reliance on the optimization of cloud and edge computing. Secondly, the integration of multiple technologies (such as the division of authority and responsibility between AI decision-making and human operation) necessitates the establishment of stricter safety standards and ethical guidelines. Thirdly, the speed of cost reduction for hardware (e.g., light field displays, biosensors) will directly impact the pace of. However, it is certain that as the aviation industry evolves towards greater safety, efficiency, and intelligence, flight simulators will no longer be merely “supplements to training” but will become the core hub connecting “virtual and real,” “human and machine,” and “R&D and operations.” The future sky may very well be held safer and wider by these “digital flight laboratories.”